- Home

- Paul Burman

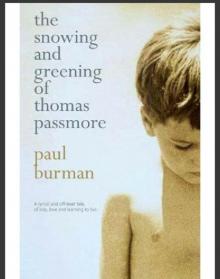

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore Page 9

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore Read online

Page 9

The grass is dry, knee-high and sprouting seed – suggesting early autumn – and laps against a cluttered sea of sinking headstones. Most of the gravestones are ancient, weathered and covered in lichen, and their inscriptions have been redrafted by the seasons. Some are sinking dangerously from the upright, like the wreckage of abandoned ships, and though I sense this place is a long way from the ocean, something tells me I might comfortably drown here.

We’re treading a worn path, the other mourners and I, through the graveyard, towards the lych-gate. The interment has taken place already and the day will now be spent over sandwiches, whisky and tea, mourning our loss, trying to celebrate a life – except I don’t know whose funeral it is. My dream has thrown me into the middle of events.

It’s only when I stop and allow the others to walk past, so I can peer beyond their sombre suits, their smothered silence, the shuffle and scuffing of their polished shoes, and try to find someone I recognise, that I notice Kate’s parents at my side. Mr and Mrs Hainley.

Kate. She can’t be dead. How the fuck has this happened?

It’s time to speak. It’s time to try and change the subject of the place. It’d be a happier story if it was my father I was laying to rest, or Brian. Not Kate.

“She can’t be dead,” I try saying. “It’s not possible.” But my voice finds no sound and I know why I might let myself drown here, out of all depth. I might’ve learnt to live without her, always believing that one day, however much later, I might see her again, but I’ve never counted on having to live in the knowledge that she no longer exists and that she’s absolutely gone from my life for all time. It’s a notion of death and loss that still scares me shitless. It’s the worst kind of eternity; a void stretching through infinity.

Kate’s mum turns to hug me and her dad overcomes his weariness to nod in the direction of the church vestibule. It’s the most generous of gestures.

Somehow they’ve told me that if I leave this procession of mourners and walk alone into the dark shadows of the vestibule, I’ll find Kate waiting. If I find her, then I might persuade her that this funeral isn’t for her and she’ll be alive again. It’ll become someone else’s funeral instead, such as her mum’s or dad’s or someone’s, but that’s okay because it’s too painful to outlive your children and no parent should be put through that.

“Thank you,” I try saying, and they limp towards the cortege of cars.

The vestibule is cold, damp and so dark it might have become night in the second it’s taken me to arrive there, and I can’t see anyone. All the same, just as I’m worrying I’ve missed her, a figure in black separates itself from the thickness of the dark and slides next to me. With the movement comes a shift in the cold dampness, so that it stirs around me before settling.

Kate.

Though cloaked and hooded in mourning, and even though her face is paler than it’s ever been, I know this is Kate. I reach to hold her hand, to lead her out into the afternoon light, but she won’t or can’t.

“What’s the matter, Kate?” I begin, but she flickers and fades at each word I speak, and I have to stop. How can I persuade her to stay without losing her completely?

I try again: “Why –?” But daren’t utter another syllable.

Reaching out to touch her and to stop her looking beyond me, she dissolves into the darkness swamping the vestibule and I lose her all over again.

Again.

The swell of grief that swamps this dream washes me awake and I struggle to untangle a sheet from my face. Elin stirs, turns and stretches an arm across my chest, and I try enjoying her closeness, hoping it might buoy me up, but it pins me down instead.

“Too hot,” I say and move away.

It’s then I listen for the sounds that might be the rushing of traffic on a motorway or the rolling of endless train carriages along a track, but which will really be the crash of waves on the beach, resonating across the front verandah outside our bedroom window. I hear nothing. Not a murmur.

The curtains hang limp at the open window.

Sliding out of bed, I stand in my boxers and peel back one curtain. The night-street is suspended in a milky sea-mist and there’s not a whisper of a breeze; only the ghostly silhouettes of trees, shrubs, the picket fence, a car parked in a neighbour’s driveway… until I see a black swan standing in our front garden, by the gate.

Wiping the glass clear where I’ve fogged it, I hold my breath and try not to blink, and wait for some movement.

“Elin,” I begin, but then remember how, after pruning the wattle and grevillea last weekend, she dumped a pile of weeds in that very spot.

I look away, then back. No swan, just a mound of twigs.

In the morning, the sea-mist lays drawn across Dungarvan like the finest of drift nets, capturing the day and holding it still. The streets, the dunes, the beaches, the river, the outlying paddocks and farms – all will be blanketed in its filaments for an hour or two of suspension, until the sun rises higher, bolder, and its warmth generates a current to stretch the mist out and dissipate it.

“You’re up early,” Elin says, entering the kitchen and making for the kettle. She lifts it, testing it fulness, then switches it on. “And you look like shit,” she laughs.

“Thanks. You too.” There’s a half-empty bowl of cereal in front of me and I’m dragging the spoon through the milk in figures of eight, steering a course between raisins and almond flakes.

“Couldn’t you sleep?”

“No. Bad dream. It woke me. Couldn’t get back to sleep. Thought I might as well get up and steal a march on the day.”

“And have you?”

“What?”

“Stolen a march on the day. It doesn’t look like it. You look wrecked.”

“Another cup of tea might help.”

She sluices the stale tea slops down the sink and rinses the pot with hot water.

“What was it about, your dream? You could’ve woken me.”

My dreams of Kate are always vivid. Twenty years on. And often share common elements: I’ve found her after a long search, she’s hurt but I can’t help her, she’s speaking a language I don’t understand, when I talk to her she disappears, but this is the third dream on this theme in as many weeks.

“I forget,” I say. “Death, I guess. Loss, perhaps.” And, to stop the conversation there, I ask: “Are the kids awake? Maybe I should get them up.”

“Or we could enjoy five more minutes of peace.”

Holding my spoon, I return to the thoughts I’ve woken with: how can I find out where Kate now lives, and how can I make sure she’s okay? She won’t necessarily need to know about it of course. Maybe I’ll get lucky by ‘Googling’ her on the internet, but what if there’s nothing there?

The water in the kettle boils and Elin pours it over fresh tealeaves. The steam billows and rolls from the kettle, from the teapot, up to the window and across the glass, fogging it over.

The mist rises and dissipates, but the sea remains mirror-flat all day and so invitingly clear it tempts us into bracing ourselves for the first swim of the season; to plant our footprints in the sand and splash out towards the reef.

Elin makes room on the garden table for a plate of uncooked sausages, a plate of burgers. She slides the salad bowl across and rearranges the tray of skewered vegetables, then pushes the bag of pulpy white sandwich loaf until it hunches over the salad. One of the beer bottles teeters against the pile of cutlery, then balances again neck-to-neck with another. As the gas flares, I pour oil onto the cast iron plates and spread it with a spatula.

“We need a bigger table,” she says.

“You always make too much food. The size of the table’s got nothing to do with it.”

“Better too much than too little.” She hands me a beer. “Can you open this?”

“I guess the kids are hungry. All that swimming.” I wave my hand close to the surface of the flat-plate to test the heat, then turn down two burners.

“First swi

m of summer,” she says, and takes a gulp of beer. “That’s good.” She combs fingers through her damp hair, straightening the knots – always a dirtier blonde during winter and spring, and the dampness brings that out, but by the end of summer it’ll be bleached a lighter tone of corn altogether. There’s sand on her feet, salt on her lips. “The kids are ravenous. They’ll eat the lot.”

And with that, from their bedroom at the other end of the house, comes the first bleating appeal in an argument.

“Mum,” Elspeth calls, “tell her she’s got to take her wet towel out. Not leave it on the carpet.”

Elin raises her eyebrows, mouths the word ‘hungry’ and heads indoors.

Ten minutes later, we’re all hunkered round a table crammed with plates and glasses, bottles and food, and the sun’s still high and grinning with heat. After the first blustery week of December, summer’s arrived in style. Snorkels, masks, fins and two wetsuits hang from hooks at one end of the back verandah, still dripping. In several days, the school year ends and the kids’ll have five weeks of summer freedom, to snorkel and surf, sleep late in the mornings, stay up at night, see friends, be outside, and with Christmas thrown in too.

“Heaven,” Elin observes, then licks a speck of sauce from the corner of her mouth.

“Bliss,” I agree, reaching for my beer. “It’s been a beautiful day, but so still.”

“Not in my classroom,” she says.

“We had to do a test,” Tamsin begins, but from across the paddock and dunes, less than a kilometre away, we hear the sudden change in tide.

Often when it happens like this, it’s like someone switches a machine on or turns the volume up. For hours on end it’s so quiet you become oblivious to it and you might be anywhere, but then it announces its presence again and you know there’s this awesome, pristine, untamed other world just a walk away – just a dive and a splash away.

One wave roars, crashes, marking an abrupt shift of rhythm, and the symphony of the surf begins again. With it comes the faintest suggestion of a breeze, to which the wetsuits twist on their coat-hangers in a light dance, and the snorkels and masks spin. Except for Daniel, we pause in our eating to listen, then smile as the new rhythm establishes itself, and the girls giggle.

“What?” Daniel says as he looks up from his plate and reaches for another slice of bread, another sausage, a dollop of sauce.

And then the phone rings.

Elspeth runs to answer, leaving a clatter of chair legs and the slamming of the screen door in her wake.

“Careful,” Elin calls.

Within the minute, Elspeth shouts back: “Dad, it’s Annette.”

It’s not even seven in the morning in Britain, and bitterly cold and dark for another hour. She rarely phones – we rarely talk – except on birthdays, and Elin and I both frown.

The phone line is poor and for a moment I hear a gale blowing, but it’s just the hollow crackle and echo of a bad connection.

“Mum’s ill,” she says. “Very ill. The doctor’s really worried about her. Andrew and I both are.”

“What? What’s happened? What’s the matter with her?”

She attempts to muffle the phone and I hear the muted sound of her blowing her nose.

“Are you okay?”

“It hasn’t been easy. But Andrew’s been good. Very supportive.”

“What’s the matter with her, Annette? What’s happened? When did this happen?”

Leaning in the doorway, Elin whispers, “Your mum? Is she alright? Ask if there’s anything we can do.”

“She was a bit poorly for a few days,” Annette replies. “I thought it was a cold, but then she got worse. The doctor thought it was pneumonia to start with, but they’re testing for Legionella or something now. The thing is, they’re worried about her kidneys.”

“When? When was she admitted?”

“Yesterday morning.”

She could’ve phoned sooner – much sooner – but I know why she hasn’t.

“Her breathing’s not good,” she continues. “But it’s more than that. She’s let herself get old very quickly.”

“Old? She’s only sixty-something, Annette.”

“I know. But it’s like she doesn’t want to get better. Not yesterday anyway.”

“And they’re worried she won’t make it?” I ask. “That she won’t survive? Really?”

“Don’t say that.”

“Isn’t that what you just said? I’m asking you.”

“It’s the way you say things, Thomas. Like you don’t care. They don’t know everything.”

When I fail to bite back, she says, “I don’t want to argue. I’m tired. I’ve been up most of the night worrying about her. You don’t have any of this.”

“Okay,” I say. I put one hand on the kitchen bench and take a breath, then I pull a face at Elin, who stands opposite me frowning. “She may well get through it, Annette. She’s always been a fighter and tough as old boots.”

“I’d like you to be right, but I’m not sure. She wasn’t coping well yesterday. The doctors and nurses were worried. I’ve never seen her like this before. She’s always been so strong and… you know.”

“Cantankerous,” I suggest.

“Spirited,” she says. “Anyway, Andrew and me thought we should let you know, so that you can come if you want, before… before…”

Again, I hear the emotion in her voice, the muffled sob.

“Thanks. I appreciate that. I do. Can you hold a second? I need to speak with Elin.” Placing a hand across the mouthpiece, I explain: “Mum’s sick. Very sick by the sound of it. Annette’s in panic-mode. She and Andrew say I should go over there to see her. The doctors –”

And wonderful Elin, without hesitation, says, “Go. Say you’ll be there as soon as you can.”

“How?”

“Compassionate leave, unpaid leave – it doesn’t matter. There’ll be a way. The museum can cope without you.”

Rubbing the tip of my thumb and index finger together, to indicate the need for money, I shrug. It’s a big question mark. For too many years we’ve struggled to be clear of debt and out of the strangulating grip of the bastard banks.

Again, without hesitation, Elin says, “That’s what our savings are for, Tom. Use them. We’ll have to hold on a bit longer to replace the car.”

“The car’s a dream. We don’t have that much saved. Not enough to buy a ticket.”

“Then flash the credit card. We’ll manage.”

Compassionate first, practical second. There’s never been any confusion between the two for her. It’s a beautiful quality, but frustrating at times.

Taking my hand off the mouthpiece, I say to Annette: “Of course I’ll come. I’ll start making arrangements straightaway.

I won’t be able to speak to my manager until the morning though.”

“Really?” she says.

“Of course.”

On the evening of the following day, after tea has been eaten and with the dishes waiting to be dried, I’m kneeling on the carpet in Daniel’s room, surrounded by an open suitcase, a flight bag and a money belt, when Elin pushes open the door. In front of me is a bundle of about fifteen green envelopes, tied together by a piece of red cord. At the sound of her footsteps, I fold the letter I’ve been reading and push it back into its envelope.

“Do you fancy a walk soon?” she says. “I need sea air.” She props one hand against the door frame and massages the other into the small of her back; then moves her head in a slow, deliberate motion from side-to-side, easing some of the tension in her neck, her shoulders.

“You look the way I feel,” I tell her. “A walk? Yeah, that’d be good.”

It’s been crazy trying to arrange such a trip at short notice, but I’m set to fly from Melbourne in two days.

“What have you got there?” she says.

“Nothing. Not much.” I slide the envelope into the bundle of other envelopes. “The past.”

“Love letters?” she

suggests and laughs, squinting to recognise the writing.

“Yes.”

“From me? Did I write that many? I don’t remember.”

“From you and Kate.”

“Do I profess my undying love for you?”

“Possibly.”

“Can I read one?”

“One of the ones you wrote?”

“Yes.”

Reaching into the suitcase, I take out a second, smaller bundle of letters. These are held together by a length of gold ribbon. The top one, which I draw out, is in a white envelope and still scented.

She takes the letter and sniffs it, but doesn’t read it. Nodding at the other bundle, she says, “Were all those from Kate?”

“Yep. I found the whole lot stashed here. Plus all this stuff.” I pull out a bag of badges, a couple of old wallets, a collection of pre-decimal coins, a collection of postcards and the corn dolly.

“The corn dolly – I remember that. We used to have it hanging up.” She draws a hand across her forehead, pulls back a stray wave of hair. “Memory lane, eh?”

“Pure nostalgia. It’s a trap. Are you going to read that?”

She’s still holding the letter.

“Did I ask you whether you fancied walking down to the beach?”

“Give me ten minutes. I’ll put back the stuff I don’t need.”

She hands back, unread, the letter she wrote eighteen or nineteen years ago and continues massaging her back. “I’ve done the lunches,” she says, and heads down the hallway.

I pick out the corn dolly and put it with the flight bag and money belt, then shove everything else from the suitcase onto the topmost shelf of the wardrobe.

SIX

I know this beach, with its rock-pools, pebbles and driftwood. It’s close to Elin’s parents’ home in Cornwall and she brought me here from London that first autumn together. Sure enough, when I look over, a young Elin walks to the side of me, kicking sand, tossing pebbles; she’s twenty or twenty-one maybe. The sea is the colour of granite and the sky is rusty-veined quartz, and between them they’re grinding the day smooth, clean, polished.

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore