- Home

- Paul Burman

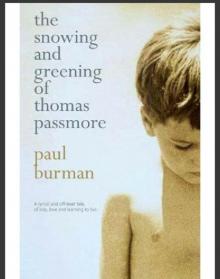

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore Page 3

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore Read online

Page 3

She half-opens her eyes.

“What are you staring at? I’m not asleep, you know. Aren’t you gonna give your mum a hug?”

“Did we wake you?”

“I was just having a catnap,” she says, and begins struggling to sit up until Annette presses a button on a remote control, automatically raising one end of the bed. Her voice is weak and rasping. “It’s too hard to get a decent night’s sleep in this place, what with the racket – the hacking cough of her over there, all these machines blipping and clicking away, and the constant fussing of nurses wanting to know whether you’re alright or not. I would be if they’d only let me get a blooming night’s sleep.”

If it’s cold outside, then it’s stifling hot inside. Annette takes off her coat, hat, scarf and gloves, but, with her pink jumper and blue skirt, is still a liquorice Allsort – just a bit more sugar-coated. I throw my coat onto a chair and peel off my jumper, realising my mother might melt into a puddle of wax on the floor if she stays here too long.

“How are you?” I ask.

“Ready for a good night’s sleep, that’s how I am. What on earth are you doing here? It was Andrew yesterday and you today. Someone told you I’m on my deathbed, did they?” She glares at Annette, who moves closer to her, sits on the edge of her mattress and smoothes a wrinkle from the blanket.

“Something like that. But I thought it was time for a visit anyway. Seemed like a good time to come.”

“You’re a liar,” she says, and almost smiles.

“How’re you feeling today, Mum?” Annette asks.

“How are my grandchildren? They’ll be almost grown-up now. Tamsin, Elspeth…’

“And Daniel,” I add. She’s always refused to use his name – my father’s name. “They’re fine. They’re good kids. Very Australian. Very outdoors, gregarious. They’d have liked to come with me – I’d have liked to bring them.”

“How are you feeling today, Mum?” Annette asks again.

“Tired,” she says. “Tired of being asked how I am. I feel like everybody expects me to drop dead any moment.”

“Don’t say that.”

“As if I should be feeling a lot worse. It’s a mystery why I’ve been brought here in the first place. It’s that blooming doctor. He needs his head read. They just needed to give me some tablets, that’s all. Maybe he gets a bonus for every patient he shoves in here.” And she begins laughing, until that brings on a fit of coughing, which makes her wince and gasp, and Annette reaches over and brings an oxygen mask close to her face. She waves it off at first, but then, when she can’t catch her breath, nods and takes a few pulls from it.

Annette raises her eyebrows at me, as if to say: told you so.

It’s too hot in here. If we take all the white hospital sheets and spread them across the ward – across the beds, drips, monitors and floor – it’d look like snow, and it’d be cooler and fresher then. I undo a couple more buttons on my shirt.

The house is cold and dark, and seems to have grown again now that I’m alone in it. After my last visits all those years back, I thought it’d be like squashing into a dolls’ house, but it isn’t. There’s even room, I suspect, for my childhood ghosts to have squeezed back into the darkness of cupboards and into the shadows under beds, or to be perched along the beams in the attic – now that I’m here.

Too many ghosts.

My earliest memories are rooted to this house and its garden, even though there was a time I’d thought to leave them all behind. Or to supplant them even, with memories of my children’s childhood, from a different time and a different place.

Wandering from room to room, turning the lights on and off, plugging in a couple of heaters to take the stagnant chill from the place, I remember going through this routine as a nervous kid, whenever I was home by myself. Except now I’m doing it with a sleepwalker’s momentum, room-by-room, until the route leads me to the kitchen, where, instead of standing on a chair to raid the biscuit tin, as I once did, I now fill the kettle and look for Mum’s jar of teabags. The mugs are in the cupboard where they’ve always been kept, but the milk’s a rancid green liquid with yoghurt-like sediment.

However, I’m putting off the most inevitable move of the lot, even though it’s the gravitational pull towards this that, seemingly, is becoming responsible for the momentum behind everything else. It’s too soon and I’m dog-tired, and how can I justify it? I wish I knew. Even so, I’m letting myself get drawn in. I’m letting it happen. As a diversion, I work out that, with eleven hours difference, it’ll be eight o’clock before I can phone Elin and the kids to tell them I’ve arrived. That I’ve arrived and have visited my mother in hospital. Mission accomplished. Almost.

Sipping bitter, black tea, I stare at the tidy suburban bleakness of the back garden before snapping the Venetian blind shut.

“What the fuck,” I say, and head into the lounge to unzip my suitcase and start rifling through my clothes for wherever I’ve tucked the address book, but the case is open and the book’s on top.

I might have returned to see my sick mother, but I’m also here for this. I know I am. After nineteen years, I’m going to find Kate again. I can’t help it. For reasons I can’t fully fathom, I need to know she’s okay and that my loss hasn’t grown any bigger. Just this. I can satisfy this, if nothing else. The momentum’s too strong to resist. Perhaps this is one ghost I can lay.

Kate.

Twenty-two years ago, when I phoned her that first time, her dad told me she was having a saxophone lesson and asked me to phone back later. I’m half-expecting the same conversation as I dial the numbers now.

I dial the first three numbers, then pause too long before dialling the rest and have to start over.

It rings once – too loud, too clear – and I hang up.

By four o’clock, night is a shroud being lowered from the sky, wrapping the day in long sleep, that snippet of death. Peering through the lace curtains, every house in the street has a Christmas tree in its window or coloured lights and tinsel. Mum has nothing. Her decorations are the dozen Christmas cards standing in a row on the sideboard. Christmas has always been a lonely and cold season in this house. Maybe, tomorrow morning, I should go to the shops and buy a small tree, a Norway spruce, and decorate it for her return from hospital.

I picture her walking into the lounge, seeing the tree in front of the French windows and having a final seizure on the spot. Night-night, sleep tight.

*

She stands over me at the kitchen door – Mum – tying the strings of a cotton sun hat under my chin, and it’s a bright summer’s morning. I feel her fingers working the bow, but pinching when she pulls it tighter.

“For goodness sake, hold still, child,” she says. And: “Now, don’t you just look handsome in that.” She leans forward to plant a kiss, but the garden’s a world of light and bird-song, and the world beckons.

Tottering down the path, I stomp through the shadow of a young almond tree, trying to splash it apart, and then jump from the path to the grass – hoppity-hop – to break into a dizzying run, round and round, discovering how to make the world spin faster, faster, faster, until tripping over the sun and landing in a heap with the world still spinning. Looking up and up and up – stretching up – and discovering a blue, hypnotic vastness that’s the sky above. An ocean.

This garden is divided into a vegetable plot and a square carpet of lawn, with a border of plants and rocks between. Mum will always like masses of colour dancing together here: the yellow of jasmine spilling in cataracts over moss-softened stones, pools of pink and mauve aubretia swimming with bees, green fountains of gladioli spurting orange and red spears. It’s forbidden to walk on the border – by my dad, my mother and, later, my step-father – but there’s a short path of stepping-stones which steal a passage through the waves of leaves and stems and flowers, linking the land of lawn with the land of lettuces, marrows, potatoes, rhubarb.

If, as a toddler, this garden is paradise then it’s a

serpent-less Eden at that. And of the sprawling housing estate being built beyond the creosote-stinking fences, which border the garden’s length and breadth, I don’t have the faintest idea. It remains a flat world with walls.

My head still spinning, I’m scooped up and thrown into the air like a bird, then caught and perched on my dad’s shoulders. Daniel Thomas Passmore. I can’t see his face, only the top of his head, but I can feel the roughness and strength of his hands, and can smell the sweetness of tobacco in his clothes and hair.

He sets me down on a patch of lawn and then he’s gone again.

Dad.

The arms of the honeysuckle stretch along the trellis, tying it in knots, and it’s laden with clusters of knotted red berries, which I begin to pluck and squeeze between my fingers – the colour of thin blood – before wiping their stickiness across the grass. Knowing they must be delicious, I long to plant a cluster in my mouth, but daren’t.

Next to the honeysuckle, a cluster of crimson pæony drowse languorously. There’s a richness to their colour, texture and scent which I’ll always find sensuous, and their languorousness and sensuousness will one future day put me in mind of the sexuality of beautiful women. Some petals, already dropped, lay wilting on the soil; other stems are expectantly heavy with tight balls of bloom bursting to unfurl and deliver their display. Each pregnant ball is a tight furl of unbloomed secret, and I begin prising with clumsy, untrained fingers to unravel the buried passage and core of one flower. When it rips, I move to an open blossom and am about to bring it to my mouth when several petals of the fleshy velvet fall at my touch. Broken that easily.

Startled and guilt-ridden, I retrieve the petals, then bring them to my mouth and bite with my front teeth, but the scent’s too strong, so I tear each of the fallen petals into strips and bury the evidence of this dissection in a hollow of dirt I’ve scooped out. This will become my first remembered experience of sensuality and brutality; my first experience of death, guilt, burial.

Playing with the crumbs of dry soil, it’s amazing that such juicy berries and soft, crimson wafers and giant honey-suckled beanstalks can be created from dirt and fed by it. I stroke my fingers through the dust and lumps – ploughing, then harrowing the soil into a new dusty fineness – then pick up a chocolate-sized crumb, sniff it, and pop it in my mouth.

Yuk! I spit and dribble the grit from between my teeth, rubbing my lips and tongue with the fingers of a dirty hand. Cheated, but wise enough to keep quiet about it, I run inside to the kitchen, where Mum’s baking a cake. I wait at her side, tugging her apron, urgent to lick the mixing bowl.

“Wash those grubby hands first,” she says, not knowing where my mouth has already been.

THREE

My dad was in glass, as they say, but got smashed when I was seven. He turned sand into glass, white light into a rainbow of colours, but was careless with himself.

My mother won’t tell me what his job at the glass factory involved. It’s one of the subjects she won’t allow to be broached. As a teenager though, I’ll discover several books stacked in a dark corner of the attic, which she’s somehow failed to find and throw away, and I’ll guess from a couple of these that he worked in the accounts department, balancing figures, income and outcome, positives and negatives, black ink and red. But he could’ve been a draughtsman or a glassblower. My dad could’ve been anything.

There’s the time he gives me a glass prism, when we spend the whole evening shining a torch beam through it at different angles, creating spectrums of colour out the other side and doing experiments. And there’s the time I think of as Our Best Day Ever, shortly before the day of his dying.

It’s a Saturday morning and we’re sitting at the kitchen table. There’s a loose edge of veneer at one corner of the table, and it’s my habit to pick at this with a thumb nail. The breakfast dishes are on the draining board, and Mum’s standing to one side of the small kitchen, slightly separate to the scene, but smiling.

“Come on, Tommo,” he says, “it’s that time of year. Sling your coat and hat on. We’ll walk down the village. You can help me choose our Christmas tree this year.” And he unhooks my black duffle-coat from where it hangs and drapes it over my head.

The previous night’s frost hasn’t thawed, and my fingers and toes, my ears and my nose, ache with the sharp cold as I run to keep up with him – stride, stride, stride – but it doesn’t matter. Two of my steps to one of his.

There’s a crowd at the greengrocery and the floor is damp and dirty. As Mr Hall scoops Brussels sprouts and carrots, or tosses King Edwards onto the scales, his breath creates foggy clouds and his bulbous red nose has a drip on the end. Dad sorts the stack of Christmas trees – Norway spruce, Picea abies – and pretends to seek my advice.

“We should get one with roots and a clump of soil on, Tommo, do you reckon? It’ll last longer.”

“Yes,” I tell him, and make a show of examining and rejecting the trees he’s passed over. There’s the slish of tyres on the salted Main Road and the grumble of motors caught behind the town bus.

“It wants to have a good shape. Not one of those spindly things. One that’s a bit taller than you, I guess. Can you see one, Tommo?”

And I point to the one he’s holding apart from the rest, which he hasn’t yet appeared to properly notice.

“That one,” I say.

“This one?”

“Yes.”

He lifts it off the ground, turns it round, inspects it from several angles. “I think you’re right. Yes, he’ll do brilliantly. Excellent choice. I’m glad you came. You know a good tree when you see one, that’s for sure. We’ll have to get you on this job every year.”

It may be a day of icy coldness, but the sun is bright.

Back home, we find a bucket and place a couple of clean half-bricks at the bottom, to stop the tree from toppling. The soil in the vegetable garden is frozen and, though Dad hacks at it until he’s red in the face, he only manages to chip away a few crumbs and to bend one of the fork tines. He rolls a thin cigarette and lights it, and I hold onto the fork for him. I’d hold his pouch of tobacco too if he let me, and secretly sniff at its snug, honeyed aroma.

“There’s not much joy in this,” he says, letting smoke drift out his mouth with his words. “We’ll never fill the bucket at this rate. We could boil a couple of pans of water, I expect, to thaw it out,” but then he remembers a bag of sand stored next to the dustbin.

Together we carry the tree through to the lounge and place it in front of the French windows. He helps me decorate the bucket with red crêpe paper and the picture of Father Christmas I’d painted at school.

“That’ll do,” he says. “Now for the real fun.”

From upstairs he fetches a large box of decorations and initiates me in the ritual of dressing the tree. First he strings the lights, spiralling them between the layers of branches, working from the tree’s tip to its base; he plugs the lights in, switches them on, isn’t disappointed when they don’t illuminate, but fiddles with each tiny, coloured globe – twisting, tightening them in his large fingers – until they all light up. Then he introduces me to the baubles and the birds. There are about twenty glass spheres to hang – some gold, some blue, some green, some pink, but mainly silver – and half a dozen birds to clip on.

“These are very old,” he says, holding one of the glass birds and brushing a finger along the fine bristles that represent tail feathers. “I’ll put these on. They belonged to Granny Potts – my grandma, your great-grandma.”

And when we’ve done that, he tugs out streams of gold and silver tinsel, which we layer from branch to branch.

He stands back and squints his eyes. “Just like snow,” he says.

I copy him and can see it myself. “It is,” I say. “It’s like snow on the branches.”

“But it’s not finished yet.”

“The star,” I announce. It’s wrapped in tissue in a separate box, but I can tell from the shape what it is.

It has a long point at the bottom and shorter ones all the way round, suggesting rays of light, and again it’s made of glass and is coloured silver, gold and blue. Dad pegs it to the tip of the tree, and there’s a different light to the room now, and the air is rich with the scent of spruce sap.

“How about that?” he says. “Perfect. Shall we call Mum?”

“There’s one more thing,” I say.

“What? We won’t fit anything else on.”

“Just one thing. Please.” I run upstairs and fetch my prism. “If you tie some cotton round it, we can hang this too.”

“No, Tommo. I think we’ve got enough. We don’t want to overdo it, do we?”

“Please.”

“Why? It’s not a decoration.”

“It’ll catch the light, if you tie it in the right place, and make a rainbow.”

“I don’t think – “

“Please, Dad.”

“Well, alright. But only this. Nothing more. Let’s see how we can do it.”

And then it’s time for Mum to admire the magic.

Christmas is just four days away and he’s late home. Not so late that Mum’s anxious or angry, but for some reason I’m standing on a dining chair waiting at the window, pressing my forehead against the cold glass. Perhaps he’s told me he’ll bring back sprigs of holly or mistletoe from the market, or balloons.

“Come away from there,” Mum says. “Find something to do, for goodness sake, child. He’ll be home when he gets here.” And she mutters something about a traffic jam or a flat tyre.

The village bobby arrives as she’s taking mince pies out of the oven. I watch him cycle up the street, take note of our house number and clamber off his bike before it’s properly stopped, the way I’ve seen cowboys dismounting a moving horse in films. Leaning his bike into the privet hedge, the policeman blows his nose on a big, white handkerchief before crossing to the front door.

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore

The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore